The Use of Explicit and Implicit Cognitive Intervention to Combat Maladaptive Eating Habits in Children in Pakistan

Abstract

In this project we present a novel culturally appropriate prototype that aims to tackle maladaptive eating habits within children. Using the tenets of CBT we aim to provide the users with a system that is both effective and engaging. the primary function of the paper remains to gauge the differences within the engagement that exist between the explicit and implicit models of intervention that CBT posits and the design elements that may contribute to positively and negatively to engagement. To this end we conducted two studie. In the first where we explore the different ways an application can be tailored to the Pakistani context and the food choices and the scenarios that are common illustrations of such unhealthy eating habits while in the second we aimed to test the prototype for Engagement. We found no statistical evidence to support the hypothesis of one being more engaging then the other. However this paper outlines through observational data the different pitfalls and highpoints that designers may be able to avoid and achieve in order to make an application such as this more effective and engaging

Introduction

According to the National Center for Diabetes Digestive and Kidney Diseases of the United States, it is estimated that approximately one in three adults were estimated to be overweight within the United States. Furthermore, we note that one in six children aged 2-19 were reported as overweight or obese in the national survey conducted in 2015 [1]. Such a trend is not only isolated to the United States, in fact according to the World Health Organization (WHO), obesity has tripled since 1975 with 41 million children reported as overweight and/or obese in 2016 [2]. While several factors may contribute to the prevalence of the above-mentioned problem, it seems clear that though cultural differences may be important in combating the rampant spread of obesity, it seems that the trend in itself is not necessarily impeded by cultural differences. According to a survey conducted by doctor AH. Amir, it seems that approximately 50% of Pakistan's population is overweight or obese according to the WHO’s guidelines for BMI values in South Asia [19].

Obesity and its onset could be attributed to several factors which include environmental, habit-induced and health-related factors which could act in some combinatorial fashion leading to overweightness followed by obesity. While the most obvious cause of obesity could be defined as the imbalance between exertion and consumption, the problem remains multipronged and generally relies on several factors including environmental ones. It is reported that the alteration in our means of travel and thereby urban planning the lack of walking spaces within cities, the lack of government support in areas of fitness and health seem to make it difficult for people to find opportunities to exercise and could be one contributor to the environmental factor. Another factor could be access to food. With lack of availability in some cases and in other, a lack of affordability, eating “healthy” might not be available to people from all walks of life [3]. Furthermore, the genetic component also comes into play when it comes to obesity. The Prader-Willi syndrome, for example, causes obesity directly while other genetic attributes contribute to easier and quicker weight gain or slower metabolism [4].

With obesity leading to several chronic diseases, it becomes paramount for all the stakeholders, patients, doctors, and policymakers to develop mechanisms that will help in both the prevention and countering of obesity around the globe. However, we note that even with the rampant spread of obesity as an issue, limited access to healthcare solutions augmented by a lack of adherence to treatment has led to a need for secondary methodology to provide both of the above [5].

MHealth applications hence seem to provide an avenue for success within the above realms with its use increasing for patient communication, monitoring and education, the reduction of a burden for diseases linked to poverty, the improvement of access to health services and for chronic disease management [6]. This project presents a framework that allows us to incorporate Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) through gamification effectively and a mechanism that would allow for some resistance to the spread of obesity

Related Work

In order for us to discern what the current status quo is with respect to that of technological interventions present in for maladaptive eating behaviors, we must first analyze which technological interventions are most prevalent and why such is the case. Such could be ascertained by the review of existing and proposed solutions in the realm of technology

CBT in mhealth Interventions:

Mhealth interventions, specifically applications, provide utility within and beyond treatment of several physiological and psychological ailments, providing a means for engagement, an augmentation of the treatment process, and the sustenance of gains once the treatment is complete [27]. As such the use of such applications to deliver cognitive and behavioral interventions becomes intuitive. In such a vain several systems aim to deliver CBT through mHealth interventions. An example could be the work done by Shaub et al. where they designed a self-help intervention for a reduction in cocaine consumption, targeting hidden consumer groups [28]. Pramana et al. posited and developed an intervention that aimed to facilitate CBT Skills Practice in Child Anxiety Treatment, citing the increased utility of mHealth gamification as a tool to make the treatment more engaging [29]. Michelle et al. developed the CBT assistant for psychotherapy which facilitated the ‘homework’ prong of CBT by increasing engagement through multiple mechanisms. Finally, in the realm of maladaptive eating habits, SIGMA [20] provides a model for the delivery of CBT to people suffering for maladaptive eating habits. Below we explain the significance and use of SIGMA as a model.

The Sigma and ABC Model:

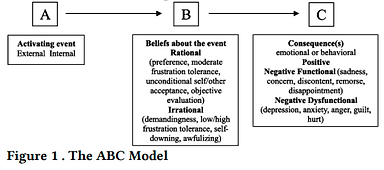

SIGMA [20], which stands for Self-help, Integrated, and Gamified Mobile-phone Application, is an mHealth gamified intervention that is informed by Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) principles, such as CBT’s cognitive ABC model, in order to reduce maladaptive eating habits. These maladaptive habits include eating in the absence of hunger or eating as a result of stress or negative emotions. [21, 22]. ABC model, i.e. Antecedents-BeliefsConsequences, states that the consequences (C), which are negative emotions and unhealthy eating behaviors, occur due to maladaptive beliefs and faulty information processing related to difficulties (B) rather than the antecedents (A) or in other terms, the activating events [23]. This concept along with some examples is illustrated in the figure 1. An example of faulty information processing is attention bias to food cues which can be combated using interventions like Attention Bias Modification (ABM) which can also be incorporated in CBT [24]. ABM aims to provide therapy to combat attentional or interpretational tendencies toward specific stimuli.[33].

SIGMA was designed to help overweight young adults in weight maintenance with the use of both explicit cognitive-behavioral intervention (SIGMAe) and the implicit attention-training intervention (SIGMAi) modules which are explained in the following section. SIGMAe aimed to remove food-related thoughts and maladaptive eating habits. This module presented a storyline to the players with the use of animated characters going through difficult situations that may trigger food cravings along with opportunities to learn to cope with the temptations and a reward-based system to encourage them to proceed. This module was based on helping the characters in making a healthy decision by choosing the most appropriate coping card out of 4 options. After making a selection, the player is given ‘healthy habit points’ as a reward and are allowed to proceed to the next level.

SIGMAi aims to address biased attention towards unhealthy stimuli by training the player to select healthy options while directing them away from the appetizing unhealthy ones. This is done by presenting food images on cards simultaneously to the player which contain only 1 healthy option, the location of which is random for each trial. The player is required to select the best (healthiest) option as fast as possible within a few seconds. In later levels, the allotted time is reduced and the images are shown to the player and then flipped, allowing the player to use their memory to select the healthiest option. With the use of these two modules linked to a scoring system along with a pedometer to track the player’s daily number of steps and a number of other features, SIGMA offers a valuable contribution towards an economical self-help tool for overweight young adults who are suffering from maladaptive eating habits.

Design and Implementation

Preliminary Study:

The preliminary input elicitation study involved contextual inquiry along with semi-structured interviews of 4 experts and 10 users. The purpose of this study was to gather information that allowed us to develop scenarios for the explicit intervention model that are culturally appropriate and hence useful by conducting a contextual inquiry within the averments where maladaptive eating habits are most enabled, specifically schools. Semi-structured interviews of experts were conducted who handle separate domains of child health and CBT with aims to look into CBT as a treatment and a mechanism for mapping CBT principles onto our intervention and also ascertaining how Pakistan is culturally unique with respect to the eating culture present and the unique problems that may be present. In our contextual inquiry, we noted the unhealthy foods available for consumption while also attempting to understand the circumstances in which these foods are consumed. We also ascertained common unhealthy and healthy food choices that children make regularly in order to make an effective implicit intervention model for the modification of the user’s attention bias.

Game Design:

We developed a game that consisted of two modules, namely the explicit cognitive-behavioural intervention and the implicit attention-training intervention, both of which are explained below.

The Explicit Cognitive-Behavioral Intervention:

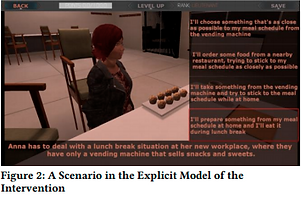

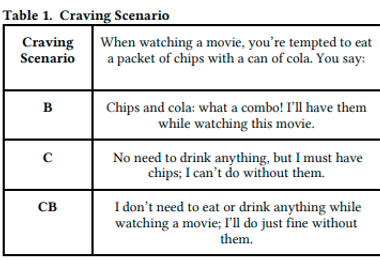

Users were presented with scenarios that involve 2-dimensional characters going through tempting situations where they have to make difficult decisions. In each scenario, the user has to help the characters choose from among three coping choices: behavioural (B), cognitive (C) and cognitive-behavioral (CB). Upon choosing the best option, the user is rewarded with points and presented with the next scenario. The scenarios are divided into three categories: Cravings, Peer Pressure and Binge-eating. These categories were decided on the basis of existing literature and interviews conducted in study 1. The rationale behind these difficulty levels is that B will always be the easiest to choose as it presents the most attractive option to the user, C will be a little harder and CB will be the hardest to choose. Words such as “I will...” have been used for B, “Perhaps”, “Maybe” and “I should...” for C and a combination of both for CB. Examples of scenarios belonging to each of these categories are shown in the table below.

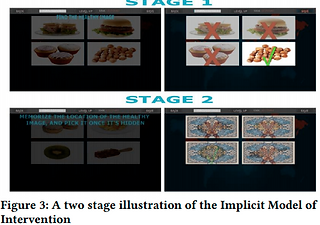

The Implicit Attention-Training Intervention:

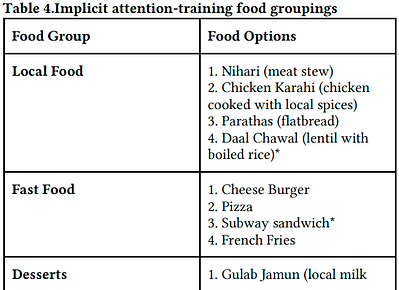

This module tests the user’s ability to select the healthiest food option out of 4 options presented to the user in the form of flashcards (images of food). This module consists of two levels: normal mode and memory mode in which the cards flip after a few seconds, allowing the user to rely on his/her memory to choose the healthiest food option. The table below illustrates an example of the food groupings designed for this module. They are divided into the following food categories: Local Food, Fast Food, Desserts, and Drinks. The healthiest option is marked with an asterisk* and was chosen based on its calorie and nutritional value

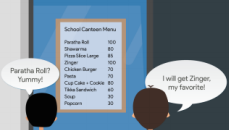

The game was designed in 2D to prevent the users from being overwhelmed by 3D graphics. Game characters were designed in accordance to Pakistani context, that is, similar dressing style including national dress, that is “shalwar kameez” was adopted. Certain styles were assigned to different characters which reflected different types of personalities. These are listed as follows:

1. Main character is depicted as an obedient but naive child who requires the player’s help in deciding what to do in each scenario.

2. Friend 1 is depicted as an overweight, aggressive child who is usually hungry.

3. Friend 2 is shown as a dominant, socially active child who is usually involved in decision-making.

4. Mother is depicted as caring yet protective who makes sure her child is getting what he wants.

5. Canteen Salesman is shown as a clever man who tries to maximize his sales by eavesdropping the children.

Attention was paid to other details as well, including “Wall’s ice cream cart” in one of the scenarios. The menu used in another scenario was a replica of the menu used in the school we visited while conducting Study 1.

Evaluation and Results

Study 2 consisted of an evaluation of the design that we implemented which aims to answer our research questions, thereby confirming or disproving our hypotheses. We surveyed user’s impressions of the intervention in terms of interest, enjoyability, perceived competence, perceived choice, pressure and tension, using IMI subscale. Furthermore, we observed the participants and also conducted semi-structured interviews to get an insight about their likes, dislikes and suggestions for improvement.

Participants:

40 English-speaking participants (30 male, 10 female, mean age: 9.2 years, range: 8-11 years old) took part in the study in a between-subject setting where each model was tested within half of our participant pool. The choice of the number of participants was directly chosen from Mason’s guide for sample size for qualitative studies [32]. Participants consisted of children who were aged 8-11 since such an age is a part of the concrete operational stage of cognitive development theory of Jean Piaget [26]. In the pursuit to minimize variables, our sample consisted of children from similar socioeconomic backgrounds.

Findings:

Engagement and Survey Results:

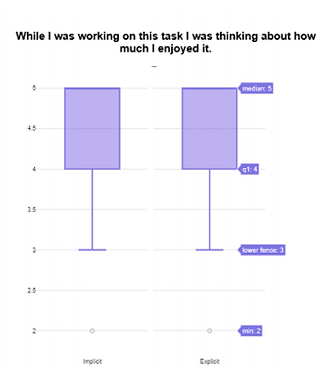

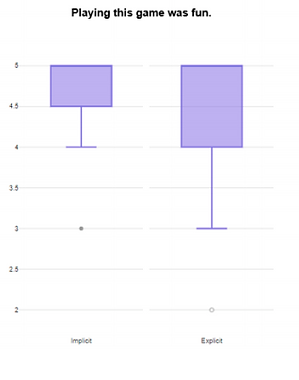

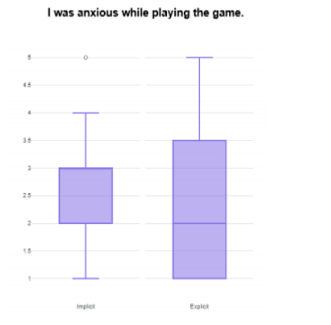

In order to analyze our Engagement Survey results, we plotted box plots of the responses received in these four engagement categories: Interest and Enjoyment, Perceived Competence, Perceived Choice and Pressure and Tension. Moreover, in order to see if a significant difference existed between the engagement level of the Explicit and the Implicit versions of the game, we conducted t-tests for each engagement category with significance level set to 0.05, the results of which are shown in Figure 13. One of the children did not complete the Explicit game, so he did not fill out the survey and hence his response is not included in the analysis.

Interest and Enjoyment:

Figure 12 summarizes responses to the Interest and Enjoyment statements in our Engagement Survey via box plots. The median score for the statement “While I was working on this task I was thinking about how much I enjoyed it” was 5 for both the Explicit and Implicit versions of the game, which shows that both versions of the game were equally enjoyed by the children. Similarly, children rated the statement “Playing this game was fun” very highly (Med = 5). Only one child gave the statement a score of 2; it was observed that he found the use of earphones while playing the Explicit game rather annoying which affected his enjoyment level of the game. The statement “I thought this game was very boring” received a negative feedback on average (Med = 2 for Implicit, Med = 1 for Explicit). Thus, overall both the versions of the game fared well in terms of interest and enjoyment. The t-test that we conducted for this category (t = 0.202, p = 0.841) also shows that that no significant difference exists in the interest and enjoyment level of the both the versions, hence validating our box plot results.

Perceived Competence:

Ten of the twenty children felt that they were competent in the Implicit game as they rated the statement “I think I am pretty good at solving this game” very highly; they were observed to get above average scores in level 1 and level 2. Seven children felt indifferent towards the statement, and three children rated it poorly owing to their low scores in the game. In the Explicit version, on the other hand, sixteen children rated the statement highly, one was indifferent, and two children gave the statement a score of 2. This shows that more children found the Explicit game to be easier than the Implicit game. However, the statement “I am satisfied with my performance in this game” was well received in both versions of the game as shown in Figure 14 (Med = 4 for Implicit, Med = 4 for Explicit). A t-test conducted for the statements in this category also showed no significant

Perceived Choice:

As this study was conducted in a controlled setting, all of the children were asked to play the game; they did not choose to play the game themselves. Hence, the median response to the statement “I played this game because I had no choice” was 2 for both the versions of the game and our t-test (t=0.337, p=0.738) also showed no significant difference between the two.

Pressure and Tension:

Only five children who played the Explicit game and four children who played the Implicit game positively responded to the statement “I did not feel at all nervous while playing this game”, which shows that most of the children felt nervous when playing the games for the first time. However, when asked to rate the statement, “I was anxious while playing this game”, the median rating was 2.5 for the Implicit game and 2 for the Explicit game, revealing low anxiety levels in children playing both versions of the game. The rating for the Implicit game was slightly higher as it was observed that children became a bit anxious while playing level 2 (the memory game) of the game. The results showed positive responses to the statement “I felt pressured while playing the game”. According to our observations, the time constraints in the game were the main cause of the pressure being felt. Moreover, a t-test was conducted to see if there were any significant differences between pressure and tension levels in the Implicit and Explicit versions. It was observed that there were no significant differences (p=0.111)

Post Exposure Evaluation:

Here we present a thematic analysis of the results we obtained from the semi-structured interviews conducted.

Decision Making:

In the Explicit game, seven children said that they liked the scenarios and the questions asked. P2 said, “I liked the questions asked...the choices were good” and similarly, P5 said, “The questions were very interesting”. P36 liked making decisions on behalf of the characters in the game as he explains: “I was making decisions for the child and that felt really good”. However, P5 complained that “I used to forget the questions when the answer panel came”. Some children really liked the concept of familiarity incorporated into the game which helped them make decisions much more easily. They were able to relate to the scenarios and the food in the game, for example, P7 stated: “I liked it when Mcdonald's was shown. I like to have nuggets and french fries from there, but I know Daal Chawal is healthy. I also liked how there was biryani at the wedding”. Similarly, P9 said, “I liked the ice cream scenario as I really like chocolate ice cream”. P33 could relate to the scenario in which chocolates were to be resisted, as he reported: “We had a similar competition at home with chocolates”. In the Implicit game, some children found it hard to find the healthy food option from the four options provided. P15 said, “I wasn’t familiar with all the food options. The food pictures should be changed so that the game becomes easy”. Moreover, P19 stated that she “didn’t think that the unhealthy food shown was actually unhealthy”. P17 found the pictures to be very similar: “It was hard to differentiate between similar pictures”. P29 suggested that “hints should be given” in both levels of the game. While most children found level 2 (memory game) of the Implicit version challenging, some actually enjoyed it a lot. P17 said, “I really liked level 2 where the food disappears”, and P23 reported: “I enjoyed how the picture flipped and I had to remember where the sandwich was”.

Reaction to Game Characters:

When asked about game characters in the Explicit game, responses included, “I liked the characters and the colors” and “I loved the cartoons; they were telling good stuff”. When specifically asked if there should be more characters in the game, P6 suggested: “Girl characters should be there like in Barbie games”. However, P9 and P7 said that no more characters should be added. P9 said, "No more characters should be added, no pets should be added, only 2-3 characters are enough, else I will get distracted."

Furthermore, some children did not particularly enjoy characters in the peer pressure scenarios, stating: “I did not like the angry friends, they should be more understanding” [P4], “I did not like it when boys were fighting with friends” [P7] and "I did not like it when the friends asked the kid to buy food with them, he had had his lunch so he should have been left alone" [P9].

Time Duration:

While most children found the time duration of the Explicit game to be fine, P2 and P4 found the game to be lengthy. On the other hand, in the Implicit game, some of the children found the time given to be less. P11 complained: “I did not like the game as it was very fast”. P17 also suggested that “more time should be given in both the levels of the game”. P12, however, specifically liked the game because of its “quick nature”.

Rewards System:

Currently, both games have a points scoring system. However, many students gave suggestions to improve the rewards system to make the games more engaging. For example, P7 suggested that “You should get hearts when you do a question right as in the Barbie games”. P8 came up with another interesting proposal: “We should get stars, trophies and stickers upon getting a question right”. P9 suggested the idea of including a competition with others in the game and giving away “first, second and third positions”.

In the end, children were also asked if they would like to play the game again and 15 children who played the Implicit game and 15 children who played the Explicit game, all expressed interest and eagerness in playing the game again.

Discussion and Conclusions

Discussion:

In this paper we presented three hypotheses, each attempting to provide some insight into the engagement and the utility of both the models presented. We aimed to discern the importance of both intervention models, reviewing our interviews and conducting an engagement study with children in the 8-11 age group. The following is an analysis as to our findings with respect to each research question and a corresponding hypothesis.

With our first research question with respect to the relative engagement of the two models, we found very little to no differences in the reported scores within enjoyment, interest, perceived control and perceived tensions which lead us to accept the null hypothesis that both the options were not statistically significant. This meant that the engagement reported by both groups remained largely invariant. Such could be due to a myriad of reasons. Firstly, the novelty of the application in both explicit and implicit interventions may have had an impact since there are no similar products within the mainstream mobile market places which might lead to the results becoming obfuscated, which leads us to the second possible reason. It is possible that the analysis might require multiple sessions and extended use before a statistical difference can be seen.

The children were engaged by the application in different ways wherein our observations we noted that some users got involved in the narrative to the extent where they forgot to share their feelings since we encouraged a think-aloud approach to our test. P30, for example, got completely involved in the game to the extent that he went silent before remarking at the end “..I wanted to make the right decision for the child”. This showed that the scenarios built in the application achieve high relatedness which contributes towards motivation and by extension engagement. However, a more active form of engagement could be seen in some users as in the implicit implementation. As the users who used this application remained largely excited, regularly fist-pumping as they got their options right, P27 wanted to “Hi-five” one of the interviewers after getting all of the food items right. Such an active mode of engagement could be due to two reasons. Firstly the timer clock that was used to generate a sense of urgency, which may have contributed to the excitement of the intervention. Secondly, the instant gratification through the quick selections of the right answers and the opportunity for redemption within the same flow may have been the causes of the animated engagement that we observed.

However, there were signs that statistical variances may occur over time. Some users' interest tended to taper off as the explicit intervention moved on. The lack of customizability in terms of narrative speed meant that for many the game seemed “slow“ [P33] or “slightly repetitive by the end” [P35]. Such a trend could be exacerbated if the use of the explicit model of intervention is prolonged which could lead to a drop in engagement. We then posit the use of gamification elements presented above along with improvements and customizations that can be done by the user in order to provide multiple avenues of interest and thereby engagement.

For the implicit model, we saw children having some issue with the food items where many had trouble distinguishing the food items on the screen while others felt that there was less time to memorise the location of the items before the card flipped saying that “it flips to early for me to remember what was where” [P27] as such similar customizability provided in the implicit model with respect to the game flow and time parameters could result in a more robust experience.

Limitations:

This project faces a number of limitations in its current state. Firstly, we note that our sampling may have had some issues. With our boys outnumbering the girls 4 to 1, we inadvertently ended up developing a study which reduces female voice which may have skewed the results. Furthermore, while we took measurements for weight and height of each individual user however did not use a BMI threshold to exclude normal children. Furthermore, we note that the length of the engagement study itself maybe a limitation since we were not able to find statistical differences within engagement even when our observational data showed that there were some elements of both models that caused problems to children while using the intervention.

Moreover, we feel that a broader diversity of scenarios and characters could have been inculcated in the game itself which may have impacted relatedness in the case of some children who might remain demotivated to modify their own eating habits.

Finally, this study does little to measure the effectiveness of either of the intervention which perhaps is paramount to the selection of one model over the other within the clinical setting. Such might be the subject of the future works Highlighted below.

Future Work:

Future work may entail progress in three key aspects: the game, the study and then the inquiry in order to get further insight. For the game, work may be done in order to provide the customisation that some users desired while also providing character personalisation. An in-game reward system in the form of currency badges or stars may aid in continued engagement while the inclusion of a more diverse set of scenarios and food options may aid improved efficacy.

Which brings us to the study. We feel that a longitudinal study within a clinical setting is required in order to accurately gauge both the efficacy and the long term engagement of the individual models of intervention while also keeping track of the individual's’ behavioral and mental traits in order to get better reasoning for the engagement of the child within the model. Finally, exploration into different applications of both models could be looked into. With different types of narratives being explored in order to look at the comparative efficacy that both provide. A look into continuous narratives which utilise the butterfly effect may be looked into for this task. Similarly, for the implicit model, a view of different games that may be used in order to retrain attention bias may be looked into in order to gauge alternate applications of each model and their respective advantages and disadvantages.

Conclusion:

In this study, we have looked at two intervention models employed by CBT within combatting maladaptive eating habits. We have developed a game that uses these concepts within a culturally relevant and age-appropriate framework. Through this prototype, we aimed to discern the differences in the form of engagement that occur within the use of both models. As such no statistically significant variant results could be ascertained. Such leaves the door open for further work to be done within the realm of CBT and its application in mHealth applications one that we feel is paramount to be accessed and worked upon since a solution that is accessible to all and effective is the need of the time.

References

[1] Overweight & Obesity Statistics.” National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 1 Aug. 2017, www.niddk.nih.gov/health-information/health-statistics/overweight-obesity.

[2] Obesity and Overweight.” World Health Organization, World Health Organization, www.who.int/en/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/obesity-and overweight.

[3] “What Causes Obesity & Overweight?” Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, www.nichd.nih.gov/health/topics/obesity/conditioninfo/cause.

[4] “What Causes Obesity.” NHS Choices, NHS, www.nhs.uk/conditions/obesity/causes/.

[5] Sardi, Lamyae, Ali Idri, and José Luis Fernández-Alemán. "A systematic review of gamification in e-Health." Journal of biomedical informatics 71 (2017): 31-48.

[6] Marcolino, Milena Soriano, et al. "The impact of mHealth interventions: systematic review of systematic reviews." JMIR mHealth and uHealth 6.1 (2018).

[7] Wang, Youfa, et al. "A Systematic Review of Application and Effectiveness of mHealth Interventions for Obesity and Diabetes Treatment and Self-Management–." Advances in Nutrition 8.3 (2017): 449-462.

[8] Turner-McGrievy G, Tate D. Tweets, apps, and pods: results of the 6- month mobile Pounds Off Digitally (Mobile POD) randomized weight loss intervention among adults. J Med Internet Res 2011;13:e120.

[9] Burke, L E, et al. “Using MHealth Technology to Enhance Self-Monitoring for Weight Loss: a Randomized Trial.” Current Neurology and Neuroscience Reports., U.S. National Library of Medicine, July 2012, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22704741.

[10] Oliver E, Baños RM, Cebolla A, Lurbe E, Alvarez-Pitti J, Botella C. An electronic system (PDA) to record dietary and physical activity in obese adolescents. Data about efficiency and feasibility. Nutr Hosp.

[11] El-Hilly, A A, et al. “Game On? Smoking Cessation Through the Gamification of MHealth: A Longitudinal Qualitative Study.” Current Neurology and Neuroscience Reports., U.S. National Library of Medicine, 24 Oct. 2016, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27777216.

[12] Fleming, Theresa M., et al. "Serious games and gamification for mental health: current status and promising directions." Frontiers in psychiatry 7 (2017): 215.

[13] Cafazzo, Joseph A., et al. "Design of an mHealth app for the self-management of adolescent type 1 diabetes: a pilot study." Journal of medical Internet research 14.3 (2012).

[14] Imbeault, Frederick, Bruno Bouchard, and Abdenour Bouzouane. "Serious games in cognitive training for Alzheimer's patients." 2011 IEEE 1st International Conference on Serious Games and Applications for Health (SeGAH). IEEE, 2011.

[15] Olatunji BO, Davis ML, Powers MB, Smits JAJ. Cognitive-behavioral therapy for obsessive-compulsive disorder: a meta-analysis of treatment outcome and moderators. J Psychiatr Res. 2013 Jan;47(1):33–41. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2012.08.020

[16] Cohen JA, Berliner L, Mannarino A. Trauma focused CBT for children with cooccurring trauma and behavior problems. Child Abuse Negl. 2010 Apr;34(4):215–24. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2009.12.003

[17] Smith P, Yule W, Perrin S, Tranah T, Dalgleish T, Clark DM. Cognitivebehavioral therapy for PTSD in children and adolescents: a preliminary randomized controlled trial. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2007 Aug;46(8):1051–61. doi: 10.1097/CHI.0b013e318067e288.

[18] DiMauro J, Domingues J, Fernandez G, Tolin DF. Long-term effectiveness of CBT for anxiety disorders in an adult outpatient clinic sample: a follow-up study. Behav Res Ther. 2013 Feb;51(2):82–6. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2012.10.003.

[19] reporter, The Newspaper's Staff. “50pc Of Population Is Obese, Prone to Diabetes: Survey.” DAWN.COM, 8 May 2018, www.dawn.com/news/1406204.

[20] Podina, I R, et al. “An Evidence-Based Gamified MHealth Intervention for Overweight Young Adults with Maladaptive Eating Habits: Study Protocol for a Randomized Controlled Trial.” Current Neurology and Neuroscience Reports., U.S. National Library of Medicine, 12 Dec. 2017, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29233169

[21] Fairburn CG. Cognitive behavior therapy and eating disorders. New York: Guilford Press; 2008.

[22] Carter FA, Jansen A. Improving psychological treatment for obesity. Which eating behaviours should we target? Appetite. 2012;58(3):1063–9.

[23] Beck JS. Cognitive behavior therapy: basics and beyond. New York: Guilford Press; 2011.

[24] Boettcher J, Hasselrot J, Sund E, Andersson G, Carlbring P. Combining attention training with Internet-based cognitive-behavioural self-help for social anxiety: a randomised controlled trial. Cogn Behav Ther. 2014;43(1): 34–48.

[25] “Defining Childhood Obesity | Overweight & Obesity | CDC.” Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, www.cdc.gov/obesity/childhood/defining.html.

[26] Spencer, Mary Ann. “Understanding Piaget: An Introduction to Children's Cognitive Development.” Journal of Research in Education, Eastern Educational Research Association, eric.ed.gov/?id=ED055910.

[27] Price, Matthew, et al. "mHealth: a mechanism to deliver more accessible, more effective mental health care." Clinical psychology & psychotherapy 21.5 (2014): 427

[28] Schaub, Michael, et al. "Web-based cognitive behavioral self-help intervention to reduce cocaine consumption in problematic cocaine users: randomized controlled trial." Journal of Medical Internet Research 14.6 (2012).

[29] Pramana, Gede, et al. "Using mobile health gamification to facilitate Cognitive Behavioral Therapy skills practice in child anxiety treatment: Open clinical trial." JMIR serious games 6.2 (2018).

[30] Crawley, Josephine Mary. "“Once Upon a Time”: A Discussion of Children’s Picture Books as a Narrative Educational Tool for Nursing Students." Journal of Nursing Education 48.1 (2009): 36-39.

[31] Wilson, William A., and M. Cornwall. "Powers of heaven and hell: Mormon missionary narratives as instruments of socialization and social control." Contemporary Mormonism: Social Science Perspectives (2001): 207-217.

[32] Mason, Mark. "Sample size and saturation in PhD studies using qualitative interviews." Forum qualitative Sozialforschung/Forum: qualitative social research. Vol. 11. No. 3. 2010.

[33] Jones EB, Sharpe L. Cognitive bias modification: a review of meta-analyses. J Affect Disord. 2017 Dec 01;223:175–183. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2017.07.034.